The Catwoman had been a regular foe of Batman's since her first appearance in Batman #1. While not appearing as frequently as the Joker, she did pop up in at least 19 stories between 1940 and 1954, so roughly once a year the readers could count on another Catwoman story. But Detective #211's The Jungle Cat-Queen was her final appearance for almost a dozen years.

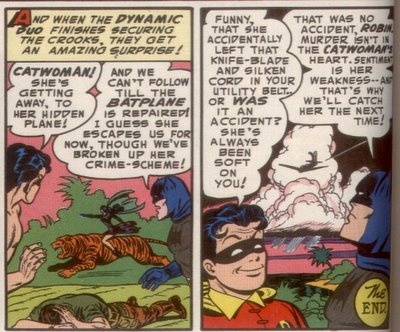

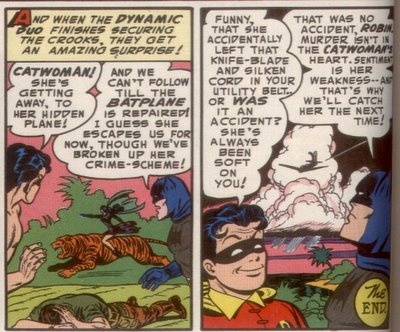

What happened? I suspect that part of it was that the Catwoman was objectionable to the Comics Code Authority. Not only was she an attractive criminal, but she frequently got away from Batman (although not with her ill-gotten gains), as in this final sequence from that story:

In many of the earlier stories, Batman seemed to intentionally help the Catwoman escape. This of course was contrary to the Comics Code Authority:

General Standards Part A:

1. Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

2. No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.

3. Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

4. If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

5. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

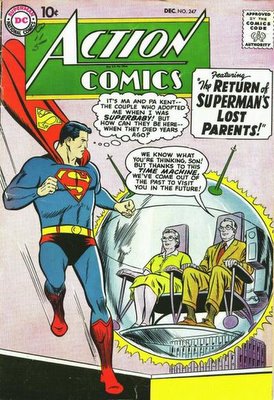

Of course, the Catwoman clearly violated #5 and #6 regularly, and so she had to go. She disappeared (outside of story reprints in 80-Page Giant #5 and Batman #176) until 1966. And when she returned, it was in a surprising location: Lois Lane #70. Why there? Well, it was November of 1966. Batmania was in full swing, and Mort Weisinger may have decided to ride the wave by borrowing Batman's female nemesis.

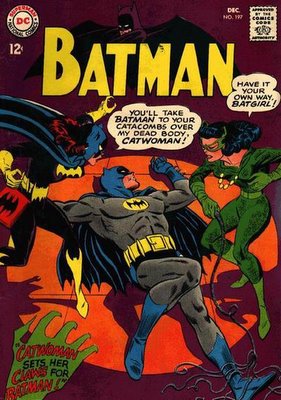

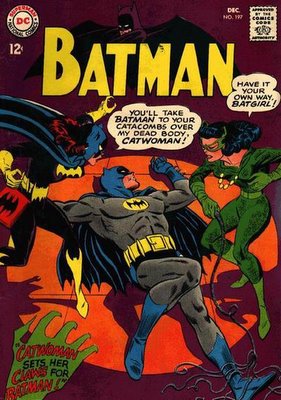

After that it was only a matter of time before Catwoman appeared again in Batman #197, although DC decided to modernize her uniform:

More about →

What happened? I suspect that part of it was that the Catwoman was objectionable to the Comics Code Authority. Not only was she an attractive criminal, but she frequently got away from Batman (although not with her ill-gotten gains), as in this final sequence from that story:

In many of the earlier stories, Batman seemed to intentionally help the Catwoman escape. This of course was contrary to the Comics Code Authority:

General Standards Part A:

1. Crimes shall never be presented in such a way as to create sympathy for the criminal, to promote distrust of the forces of law and justice, or to inspire others with a desire to imitate criminals.

2. No comics shall explicitly present the unique details and methods of a crime.

3. Policemen, judges, government officials, and respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

4. If crime is depicted it shall be as a sordid and unpleasant activity.

5. Criminals shall not be presented so as to be rendered glamorous or to occupy a position which creates the desire for emulation.

6. In every instance good shall triumph over evil and the criminal punished for his misdeeds.

Of course, the Catwoman clearly violated #5 and #6 regularly, and so she had to go. She disappeared (outside of story reprints in 80-Page Giant #5 and Batman #176) until 1966. And when she returned, it was in a surprising location: Lois Lane #70. Why there? Well, it was November of 1966. Batmania was in full swing, and Mort Weisinger may have decided to ride the wave by borrowing Batman's female nemesis.

After that it was only a matter of time before Catwoman appeared again in Batman #197, although DC decided to modernize her uniform: